More than two years later, the markets continue to show that the most successful businesses that have addressed the challenges of the pandemic are ones that have ESG practices woven into their very fabric. So, why are companies still struggling to create meaningful structural change?

As we continue into 2022, ESG related funds are breaking records and aren’t showing any indication of slowing down. However, the onset of Covid-19 has not only amplified existing challenges but also created an entirely new set of complex pressures that are being felt across all sectors. Companies now face the challenge of balancing various stakeholder interests and heightened expectations pertaining to a new reality characterised by societal impact, corporate citizenship, and future uncertainty.

With the rise of the “conscious consumer”, there is now a fear factor for companies; failure to identify environmental risks could damage their corporate responsibility, brand reputation, and financial performance. As a result, many CSO’s isolate the first pillar of ESG and adopt a ‘carbon tunnel vision’. Not only has this resulted in greenwashing through marketing efforts and PR tactics but it has also prevented companies from identifying the remarkable interdependencies within ESG, which in turn, is weakening the intentionality of the movement.

ESG is now at a make-or-break moment; it could either build or break trust in companies. We can no longer say “this is an environmental issue” or “this is a social issue” as such statements still create divisions and hierarchies. Yes, the environment is the service provider that enables our human society to exist but without social and governance, all is lost, including the environment. Yet, even when these two issues are considered alongside each other, they are often isolated, with companies setting separate goals for each sustainability dimension.

Moving forward, companies must assess social considerations through all time periods and not just solely in response to the pandemic. Research has shown that good environmental practices are often good social ones, and vice versa. So, by acknowledging good and bad historical practices, companies will acquire a heightened awareness of the social and financial costs associated with the systemic nature of the ‘E’ and ‘S’ pillars. For instance, remote working has gained incredible traction with companies aiming to improve employee well-being and reduce their environmental impact. Moreover, reflection will inspire companies to acknowledge and value the symbiotic relationship between people, society, and the planet.

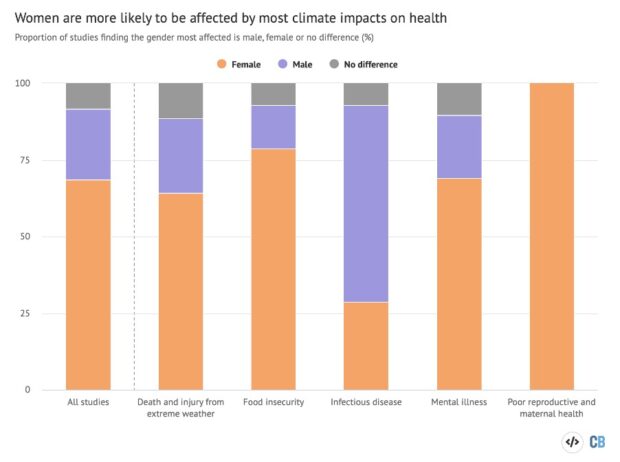

From wildfires and hurricanes to tsunamis and heat waves, there’s no denying that climate change is one of, if not the most pressing environmental challenges of our time. Almost everyone has felt the effects. Yet, they are not being felt equally. Throughout history, women have struggled with human rights issues more than men. It is these long-standing gender inequalities that have created disparities in information, mobility, decision-making, problem-solving, and access to resources training, and health care.

Women produce more than half of the world’s food. This not only leaves them more vulnerable to droughts, forest fires and floods but also forces young girls to leave school to help their mothers. Women and children are 14 times more likely to be injured or die during a natural disaster than men with the mortality rate of women even going as high as 79% of total deaths. So, whilst climate change and gender equality are two distinctive and complex issues, they are certainly not unrelated. It is essential that gender is considered and evaluated in order to successfully and sustainably mitigate, adapt, and build resilience to climate change globally.

Women not only feel the effects of climate change more acutely than men but are also raised to be more socially conscious than men. From early childhood, society conditions us to view empathy as a feminine trait and subsequently, caring about environmental issues as feminine. As a result, men are often fearful of being conscientious as they believe it will undermine their masculinity. A 2019 study conducted by researchers at Penn State found that men could be disinclined to carry a reusable shopping bag in fear of being perceived as gay. Moreover, the widespread disparity between ethical choices made by men and women has created an Eco Gender Gap; 71% of women try to live more ethically, compared to 59% of men.

Two zero-waste online retailers have endeavoured to address this issue by using gender-neutral marketing but claim that 90% of their customers are still women. Whilst women are more powerful consumers, this gap is largely perpetuated by gender stereotyping; women are still largely responsible for the domestic sphere. As a result, it seems that women not only face the responsibility of being caregivers in the home, but of the planet as well. Yet, it is in fact this disproportionate impact that uniquely positions women to lead the fight against the global climate crisis; it is reflected not only in women’s attitudes but also their actions. One is the youngest ever congresswoman and the other a Swedish teenager. Together, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Greta Thunberg form two of the most compelling voices in the climate activism community, galvanising millions with a clear message: actions speak louder than words.

Despite studies showing that female policymakers are more sensitive to community needs, better at handling crises, and work in a more bipartisan way, women continue to be outnumbered by men 2:1 in positions of power and less than 1/3 of UK’s top jobs are filled by women. The people who hold the top jobs in our society have enormous power to shape our democracy, culture, and economy. Therefore, it is critical that more women occupy leadership positions as they’d be aptly positioned to implement gender-responsive budgets that ensure women are supported on a national level, ensure more girls receive an education to increase work opportunities and flexibility, and push for environmental policies that include humanitarian and disaster risk reduction plans.

In a year that saw U.S. billionaires gain one trillion in wealth throughout the pandemic, Covid-19 would further economic inequality, highlighting the inherent problems within capitalism. Moving forward, boards must meet new expectations. As ambassadors of corporate purpose and values, boards must build stakeholder trust by setting a consistent and transparent tone from the top. They must not only work more closely with management on assessing pay practices and rethinking compensation policies but also on strategy, risks, societal engagement, board composition, and management’s diversity and inclusion efforts.

Effective ESG measurement is not easy; it takes time, involves complex data, stakeholders with competing ideologies, and hard to define metrics. Yet, a diversity of experience and perspective in the boardroom will see change happen more quickly. Women remain just 8% of FTSE 100 CEOs, and none are women of colour. Yet, countless studies have shown that women in senior position can be transformational, making board discussions more robust, delivering great client satisfaction, and yielding higher profitability. When women become leaders, they not only create positive change through imaginative perspectives, enhanced dialogue, better decision making, and effective risk mitigation but also in boardroom environment and culture. The addition of more female directors from underrepresented groups is likely to have a similar effect and will not only help close the gender pay gap, but also the ethnicity pay gap.

Gender inequality is so deeply embedded in society, and the effects of climate change are not easily reversible. So, asking women to solely lead the fight for sustainability completely undermines progress across E and S. Leaders must challenge societal norms and proactively encourage men to work alongside women to unite and build solidarity across the three elements of ESG. It must also be noted that the challenges of climate change are not uniform amongst all women; to recognise, understand, and address this, sustainability must be explored through the lens of intersectional feminism. This is greatly echoed in the experiences of indigenous and Afro-descendent women, older women, LGBTIQ+ people, women with disabilities, migrant women, and those living in rural, remote, conflict and disaster-prone areas.

Yet, we must also be careful to acknowledge the limitations within these analyses; treating gender as a binary excludes individuals who don’t fall into the traditional categories of “woman” and “man”. As the International Sustainability Standards Board continues to improve upon their guidelines, it is essential that they empower leaders to acknowledge the complexity and interconnectedness of the experiences and challenges faced by different groups, centre them, and work to develop integrated solutions that will improve them all. Together, Accenture and The World Economic Forum have identified 21 practices that constitute Sustainability DNA, enabling directors to effectively invest in deep metrics and build a strong learning culture. Moreover, these practices will strengthen stakeholder relationships in three ways: driving human connections, collective intelligence, and accountability at all levels.

In many ways, Covid-19 unearthed a silver lining for an evolving ESG narrative. By centralising stakeholder perspectives, companies can start developing egalitarian practices born out of collaboration and will gradually forge a virtuous cycle to revolutionise ESG. This will see a meaningful long-term effect as it will not only galvanise businesses to watch and adapt accordingly in the face of unforeseen events but will also illuminate the connection between all fights for equality, justice, and liberation.